The Iconoclast

Dan Geer has never been one to walk away from a fight. In 2003, he was fired from security firm @Stake after authoring a report released by the Computer and Communications Industry Association arguing that Microsoft’s monopoly over of the desktop was a national security threat. Given that Microsoft was a client of @Stake at the time, it’s not a shocker that he didn’t make employee of the month. Somewhat humorously, in an interview with Computerworld after the incident, Dan remarked, “It’s not as if there’s a procedure to check everything with marketing.” Somehow I think a guy with degrees from MIT and Harvard didn’t need to check-in with marketing to gauge what his firm’s reaction to the paper would be.

Fortunately for the Black Hat audience (and those of us who watched the presentation online), Dan continued to live up to his reputation. He outlined a 10-point policy recommendation (well summarized here) for improving cyber security. In the preamble leading up to the policy recommendations, he made two key points that provide critical support for his policy argument:

- The pace of technology change is happening so quickly now that security generalists can no longer keep up. Highly specialized security experts and governments are now needed to protect our information assets.

- If you want to increase information security, you have to be pragmatic and willing to make compromises. As Dan succinctly put it: “In nothing else is it more apt to say that our choices are Freedom, Security, Convenience—Choose Two.”

These points are important to keep in mind when listening to his presentation because they provide critical context for his potentially unpalatable policy recommendations.

To Regulate or Not to Regulate

As a card-carrying capitalist, I’m naturally wary of government technology regulation. But as a digital technologist I’m absolutely terrified of it.

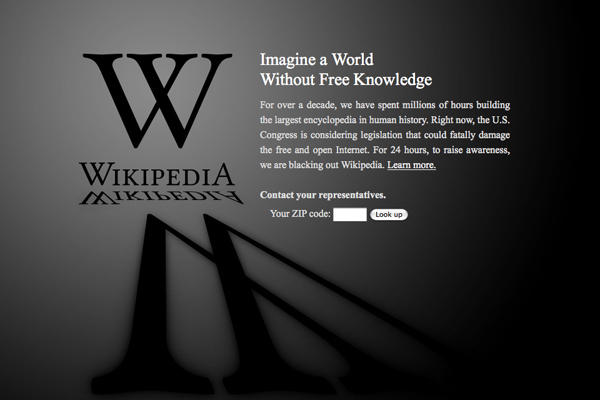

While watching congress discuss online piracy during the SOPA/PIPA fiasco in 2012, it became apparent that politicians have no understanding whatsoever about the nuances of technology and Internet use. It took a rare display of political solidarity among Internet companies (the SOPA blackout) to force congress to actually spend 5 minutes considering the implications of the legislation they were about to sign into law. It doesn’t take a computer genius to realize that removing DNS entries for entire sites that have been accused—not even convicted—of IP infringement is a terrible idea, especially when we already have legislation that enables content creators to enforce their copyright online. Under SOPA, simply linking to a site accused of infringement could have gotten you erased from cyberspace—bye bye Google and Reddit. If the bill passed, China would have been so proud of us.

Fortunately, when people couldn’t access Wikipedia for a day during the blackout, they emailed their legislative representatives, and Congress came to their senses. But the political machine itself hasn’t changed, and the dangerous technical ignorance of Congress still remains.

Given this reality, you can understand my hesitation about Dan’s policy recommendations, most of which were regulatory in nature:

- Mandatory reporting for some classes of security breaches, styled after CDC reporting requirements

- Liability for developers who deploy vulnerable code

- U.S. government payments for vulnerability discovery

- Endorsement of the EU “right to be forgotten” laws

- Mandatory open-sourcing of “abandoned code bases” that are no longer supported with security patches

- The development of Internet borders that map to nation-state borders

First of all, it’s important to remember that not all regulation is bad. Things like the outlawing of child labor, food safety, clean drinking water, and weekends were all the result of regulation.

Second, it’s essential to understand that regulation doesn’t have to be an all or nothing endeavor. In his presentation, Dan suggested a model for regulatory flexibility:

- For mandatory reporting, he recommended defining a security impact threshold, above which reporting would be mandatory, below which reporting would be voluntary

- For developer liability, he suggested giving companies an option: eliminate liability by open sourcing their code, or taking on liability by keeping their source code secret.

- For abandoned software, companies could choose to continue patching old code bases, or elect to open-source the code when it’s no longer viable to support it.

But by the same token, it’s not wonderful managing security without any regulatory guidance. PCI standards are great, but they’re not broad enough. Increasingly, contracts between companies and suppliers have security clauses. But what’s considered a “commercially reasonable” measure when it comes to security? And how does this change over time? I’ve seen dozens of security provisions and checklists from my clients, and, much like snowflakes, no two are the same.

Furthermore, history has shown time and time again that without regulation, companies will choose profit over safety. And even with regulation, bad things happen when regulatory agencies get lax (e.g. 2008 mortgage crisis, Bernie Madoff, Deepwater Horizon oil spill, Enron, the Patriot Coal mine disaster, etc.).

So, we find ourselves in a situation where companies are required to create a patchwork of individual security standards, where businesses choose to hide rather than share information about attacks, and industry feels no regulatory pressure to improve cyber security. And, adding insult to injury, the pace of technology change continues to increase, the number of computing devices subject to attack is growing exponentially, and the financial and political incentives for cyber villains are increasing.

It must be a good time to be a cyber terrorist.

Quid Pro Quo

Given this dire state of affairs, perhaps it’s time to reconsider the notion that all technology regulation is bad. Yes, Congress will make a mess of it because they don’t understand technology. Yes, regulation will make the lives harder for people like me who develop and deploy software for a living. And No, regulation will not in and of itself “fix” the problem. However, the alternative of doing nothing is far, far worse. It’s time for us to choose the lesser evil.

Dan described this choice eloquently in the abstract for his presentation: “Some wish for cyber safety, which they will not get. Others wish for cyber order, which they will not get. Some have the eye to discern cyber policies that are ‘the least worst thing’–may they fill the vacuum of wishful thinking.”

But just because we’re choosing the lesser of two evils, that doesn’t mean we can’t make the “lesser” option a little less “evil.”

Let’s take Dan’s proposal to institute liability for software developers who deploy code with security vulnerabilities. As a software developer, this concerns me for obvious reasons: since it is practically impossible to deploy bug-free code, I would always be living under a cloud of potential litigation. Not awesome.

However, I also know that the threat of liability would capture my attention. I have UK clients who fall under EU privacy laws, which do have liability provisions. As a US company, if I touch UK data I have to either voluntarily enroll in the US Safe Harbor program, or sign a contract with my client that binds me to EU law. At first, I hated signing these contracts. But by doing so, it forced me to reevaluate our security polices to ensure they complied with EU regulation. Once the policies were updated, I was glad to be operating with a greater level of PII protection.

If the US also implemented regulation with teeth, it would absolutely get the attention of US software developers, and it would almost certainly improve the security of the software being deployed and supported. Unfortunately, Americans are litigious, and unlimited liability is a potentially company-killing risk. The medicine would be worse than the disease.

But, what if Congress made a simple deal with the technology industry: “If you follow a list of well-defined security best practices, we’ll significantly reduce or eliminate the liability you would face due to a security breach in your software.” This quid pro quo would be beneficial for both parties. Consumers would get a safer Internet, and technology firms would get a cross-industry security standard (hopefully closer to PCI than Sarbanes-Oxley in length) and they would get a reasonable limit on liability. Companies and suppliers could still include additional, specialized security provisions in their contracts but they wouldn’t have to negotiate the basic terms, relying instead on pre-existing US standards.

Certainly, a national security standard like this would be insufficient to protect against all cyber criminals, and technology firms would need to do more to keep information assets secure. But, it would establish a consistent security baseline and a minimum threshold that distinguishes the negligent from the rest of us who are doing our best to keep the Internet secure.

However, even this limited version of regulation would no doubt cause consternation within the business community. People would argue that even limited liability would stifle innovation. But there are two flaws with this argument. The first is that it’s simply not true: if the big, active, commercialized monster of patent liability hasn’t slowed down innovation, why would the limited liability suggested here do so? Second, if a start-up can’t afford to maintain a baseline security standard, then do we really want them introducing their software into the marketplace in the first place?

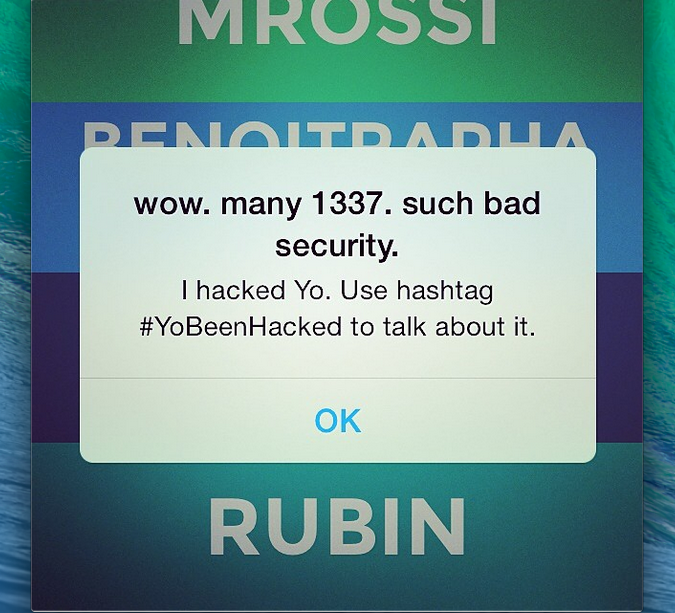

The fledgling app maker Yo is a case in point. Shortly after launch, their app got hacked by a college student. This probably occurred because Yo’s developers were obsessively focused on getting something to market quickly, rather than worrying about security. This is understandable. But the real question is: Would the world really be worse off if we had to wait a few extra weeks to send our friends a two-letter message, because Yo developers were required to spend time making the app comply with national security standards? Somehow I think we would have found a way to survive, and Yo would have still received its $1.5 million in funding after release.

No Longer Waiting For Godot

Dan had a nice bit in his speech about humility. He predicted that he would alter his beliefs after releasing them into the wild, as the debate and dialog about them unfolded: “Humility does not mean timidity. Rather, it means that when a strongly held belief is proven wrong, that the humble person changes their mind. I expect that my proposals will result in considerable push-back, and changing my mind may well follow.”

Classy. Also very smart. Why can’t we all adopt this Agile approach to policy debate, like we would for the development of software? Why can’t we propose solutions iteratively, and refactor them later as we learn more about the requirements? Instead, when it comes to politics and policy, we tend to employ a Waterfall approach, desperately clinging to our beliefs, even after the underlying assumptions in our mental “spec” have long since changed.

Well, the assumptions underlying cyber security have changed. So perhaps now is the time to refactor our approach to cyber defense, and for those of us in the business community to re-evaluate our stance against technology regulation. If we truly care about our investors and our customers, then the only sane solution is more centralized coordination to combat cyber crime, which means some type of regulation. Let’s just hope we can all summon enough humility in this matter, because the opposite of humility—hubris—is unlikely to get the job done.