A rash of cyber attacks and security news hit over the Labor Day weekend, impacting The Home Depot, Healthcare.gov, Goodwill and Apple. But at least this recent flurry of security activity is positive in one respect: it gives us a glimpse into the mechanics of real world attack scenarios. The more we can use this as a learning opportunity, the safer we’ll be. Here are a few lessons we should take away from the attacks:

1. Understand that even if you do everything right, you’re still not safe

During the first few days of the September iCloud breach, in which explicit pictures of several celebrities were hacked via Apple’s iCloud backup service, many people were saying that the victims should have used two-factor authentication to protect their information (sadly, another example the “blame the victim” mentality). It was later disclosed, however, that Apple’s two-factor authentication didn’t actually cover iCloud backups. So, even if you are one of the rare, paranoid people who use two-factor authentication, it wouldn’t have protected you.

In a similar vein, having the most secure password in the world, wouldn’t have helped the customers of Home Depot or Goodwill, who’s stolen credits cards were used in-store. If the people processing your credit cards get hacked, no amount of cyber protection will save you.

2. Monitor your bank statements daily, and your credit score regularly

Once you embrace the reality that you’re going to get hacked eventually, you can start focusing on implementing a strong Plan B. In this case, the best thing you can do is identify the breach early, and that means checking your financial activity frequently. Although you may want to consider using a separate low-limit credit card for online purchases, the recent attacks at Home Depot, Target and Goodwill appear to have compromised transactions in-store, so that wouldn’t have helped. My recommendation: Don’t bother with the special card, it’s not worth the hassle. A better solution is to use a single card for all purchases, to reduce the number of accounts you need to monitor.

3. Use a strong password—for real this time

Even though it doesn’t guarantee safety, a strong password goes a long a way, as cracking passwords is still one of the most commonly used means of attack. (And definitely don’t use a stupid password like 123456 or Password or Password1. )

But here is where I get annoyed. Yes, we all know that we’re supposed to use a strong password. But let’s face it: this advice isn’t actually useful in the real world. Do you really believe that someone without a photographic memory can manage all of these standard best practices simultaneously:

- Create a password that is very long.

- Don’t use anything you might be able to easily remember, like the names of people you know, your pet's name or dictionary words.

- Don’t use dictionary words with letters replaced by similar-looking numbers (like replacing an “O” with a “0”)—the cat’s out of the bag on this trick.

- Do use a lot of special characters and numbers that you probably can’t type without looking at the keyboard and that are difficult to remember.

- Don’t use the same password for multiple sites. Or, to put it another way: Use a unique password for the 25 different sites you access regularly.

- Change your passwords frequently.

- Don’t write your passwords down or keep them in a place that’s easily accessible.

So, basically people are told to do the impossible to manage their passwords, and then they are blamed for not achieving this when their accounts get compromised. Awesome.

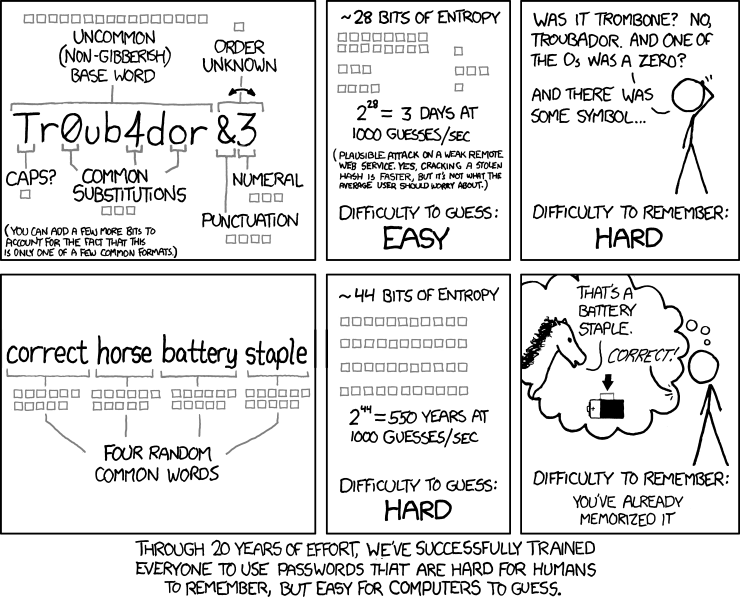

From xkcd.com

Here’s my pragmatic advice for strong password management:

- You absolutely need a strong password. This is not optional.

- Choose password length over the crazy use of special characters. Dropbox.com has a great blog post about this. It’s better to use a long string of disparate dictionary words that you can remember, than a short string of funky characters and symbols that you can’t.

- Do use a combination of upper and lowercase letters (even simply capitalizing some of your dictionary words in your long string of words is better than nothing).

- Do use numbers and special characters. I don’t go crazy with them like I used to, but I do include them.

- Vary your passwords for each site based on something unique about the site itself. It’s simply not realistic to expect people to remember a highly unique strong password for every site. Instead, devise a strong one and let it vary in a systematic way for each site. This is the best worst option.

- Change your passwords at least twice a year. This is a pain, but it will greatly reduce your exposure. If you have a secure place to store your passwords (see below), then it makes this job a lot easier.

Once you’ve committed to the recommendations above, you’ll need a place to store your passwords. Even if you use a common format, you’ll invariably have a few different versions floating around, if nothing else, because the password requirements for each site make it impossible to use a single secure password template everywhere.

Don’t keep your password list on paper. Not because it’s insecure (it’s actually probably the safest place for it) but because it’s impractical. You need to be able to access it from home, work and on your mobile device.

Don’t store your list in a password-protected Excel or Word document because they are super easy to crack.

Do use a tool designed to store passwords securely. You might consider something like LastPass, a commercial product (with a free and premium version) that stores your encrypted passwords locally and in the cloud. LastPass will also auto-fill website login fields which gives you the option of having LassPass automatically generate strong random keys for each site.

Although I think LastPass is a legit option for managing your passwords, I don’t like the idea of all of my passwords being stored in the cloud. If you make the assumption that everything is hackable, then I believe it’s safer not to store your passwords in a centralized location that is an obvious target for hackers. I also want to be able to enter my passwords from memory, so relying on a tool to memorize them for me is unappealing.

Instead, I recommend KeyPassX, a cross-platform port of KeePass, an open-source .NET keyword manager that’s been around for over ten years. KeyPass is pretty basic—it just stores a list of your passwords securely. But the very fact that it’s basic means there are less moving parts and less bugs that could be exploited. Also, because it’s open source (meaning, there are more eyeballs reviewing the code) and its been around for so long, it is much more likely to be secure. I store the KeyPass database on a cloud-based drive, which allows me to access it everywhere.

5. Use false info for security questions

We know from posts by the iCloud hacker community that they used the password retrieval feature of iCloud to gain access to private data by guessing answers to the security questions. Although there may be less information on the Internet about you than there is Jennifer Lawrence, this is nonetheless a serious security loophole.

You should use false information for security questions (maybe based on somebody else that you know) and store the answers in KeyPass (although if you need to use the password retrieval feature in the first place, you probably don’t have access to KeyPass, so storing this info there is only marginally useful). This measure is annoying and a hindrance, but it’s necessary. It doesn’t help to have a super strong password if hackers can simply bypass it by answering easy-to-guess security questions. Security is only as strong as the weakest link.

6. Keep your really private stuff, buried deep

Security expert Dan Kaminsky wrote an interesting blog post about the iCloud breach in which he discussed the tension software providers like Apple face between offering convenience on the one hand and security on the other. The two are usually mutual exclusive and a commercial software company is almost always going to err on the site of convenience, since that’s what their customers want (or at least what they think they want).

However, given the option, most people would probably opt into a higher level of security and inconvenience to protect their really secret stuff, like naked selfies and pictures of their of embarrassing navel lint collection. Credit card charges can be refunded, but the damage to your reputation if your darkest secrets are revealed cannot. I hope software providers heed Dan’s advice and give us such an option one day. But until then, we should consider taking extra precautions ourselves when handling this type of crazy secret data, such as: taking the time to understand how privacy controls work, using highly unique passwords for our really secret data, using two-factor authentication when available, sending the data using a secure ephemeral messaging service like Wickr, keeping the data in an encrypted password protected file, or storing it offline on memory stick in a safe. Yes, these practices will make it much harder for you to access this type of data, but it will also keep it much more secure.